Our culture suffers a destructive “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” mentality that presumes that who we are and what we do is just a matter of choice.

But we don’t have as much choice as we might like to think. And certainly less than we’ve been told. For starters, we have no say at all in what brain we start out with.

Nor do we pick the environments that our brains are born into where they develop their most basic maps of the world.

Our unique brain’s response to the unique circumstances it experiences is what determines who we are, long before we’re aware enough to know who that even is. It dictates our natural aptitudes, deficits, temperaments, and developmental injuries without offering us any consultation on the matter.

I didn’t get to spin the knobs to select how patient I was. Or how easily soothed. Or how fearful, angry, overwhelmed, or socially awkward I turned out to be. No more than I got to choose my eye color.

Nevertheless, there is a widely embedded expectation that, wherever the wheel stops, we can use raw drive and gutsy determination to flip any unwanted frowns upside down. We just need to want it bad enough and keep our nose to the grindstone.

But there are serious limits on how hard, long, and often any particular one of us can grind it out.

This can be a hard pill to swallow. The lore of self-determination tells us that we can always try harder and work smarter. But we can not. Though we may be goofing off when it comes to what’s expected, we’re always operating at maximum capacity in our efforts to feel okay.

We might not be getting to half the things we’re supposed to, and only half doing the things we are, but our brains, consciously or not, are always maxed out in their quest to find satisfaction. That’s how natural selection rolls. Even when it looks like we’re not trying at all.

The truth is that our real, non-fictional agency over ourselves operates wholly without bootstraps. It is a much more subtle, significantly less shame-logged cognitive ability. By focusing our attention on the things we want to change, our brains naturally detect the patterns involved and imagine ways to tweak them over time. It’s a beautiful, exciting, transforming process that depends, not on brute force, but on what we think about.

Sometimes we can reap rewards fairly quickly by redirecting our external efforts toward things that will actually satisfy us. But we often need to first effect internal change, and that takes time. The best we can do is to look honestly at ourselves to see where we are. And to get smart about where we want to be. We can only move our rudders a degree at a time and then we must wait to arrive in more serene seas. We can not simply forge ourselves into the person we want to be.

Change takes patience, prolonged focus, and brigades of emotional courage. All of which are precious gifts that may or may not be available to us at any given moment.

So.

When I finally realized that I am–and have always been–perturbingly more anxious than I ever knew, should I have somehow blamed myself?

Is it my bad that my early missteps led to ridicule and lost connections that I desperately wanted to avoid? Should I have not developed a hyper-vigilant, constant state of alarm that kept me continuously evaluating everything I said and did and might say and do?

Was there some way I could’ve buckled down and better processed the continuous stream of upsetting developmental events I experienced so that I might have ended up less adept at vacating the present moment?

Did I miss a chance to make a “better choice,” that would have saved me from responding to life’s pains by instinctively pushing my feelings down and ignoring them until I lost touch with a whole lot of what I feel and, subsequently, who I am?

Of course not! I didn’t create my body’s prehistorically optimized trauma responses any more than a turtle picks her shell. If my will had its way, I’d be carefree and happy. And socially gifted.

I would have learned how to connect when I was a kid instead of not yet. I’d be able to relax my neck and back. And I wouldn’t be self-conscious to the point of distraction. I mean, why not? But cards fall as cards fall.

Looking honestly at myself can be a bit startling. I certainly don’t love everything I see. But I can’t work on what I can’t even acknowledge is there. When shame makes me look away, I am stopped dead in my tracks, blind to myself, and unable to ponder my psyche’s patterns.

The exciting news is that the more that I’ve understood how little control I’ve actually had over who I am, the less shame I naturally feel, and the more deeply and honestly I can self-reflect. I no longer have to run off to one distraction or another. I’m not my fault.

Lately, I’ve finally started to feel myself changing. It’s still not happening on my schedule because the speed at which our brains can heal, it turns out, is also not up to us. But I’ve been able to seek help and work methodically around the edges of my developmental injuries, in whatever ways I can happen to manage, to eventually redirect my nervous system to a state of more calm and presence.

It’s admittedly odd to talk about my limited input into myself. After all, I get to choose what I do, who I hang out with, and what I want on my sundae. But when I really think about it, I don’t know why I like what I like, choose what I choose, or feel how I feel.

I might be able to backfill an explanation here, or trace an influence there, but my tastes are much more a process of discovery than of creation. I am more like a customer than a chef in the tavern of my own mind.

Delightfully, this lets me off the hook. It assures me that there is no force of will that I have failed to deploy to miraculously override the mechanics of my biochemical history and suddenly transform myself. I know I’m trying as hard as I can and that this is all I can do.

I know we all are. Even when it appears otherwise.

Without blinding shame, I am able to curiously explore who I am and WTF happened to me. I can meet my old, hurt and frightened feelings with love, comfort, and the wise guidance of the awakening adult I now am. I can see the boy who spent so many years constricted with fear, and I’m learning to calm him and thank him for getting me through it all as well as he did.

This is all cause for celebration but it is not to my credit any more than my faults are my fault. The reason I succeed is the same reason I fail. I like to call it grace, but it’s better known as luck. Our brains end up being good at some things and not so good at others.

For reasons beyond everyone’s control, it is harder for some of us to be positive and comfortable. It’s more challenging for others to connect. Some people have difficulty not bawling during job interviews. Others can not stop worrying. That’s how luck is.

I hope that it goes without saying that we must all still be fully and entirely responsible for ourselves. None of what I am saying is an excuse to do whatever you want and then plead a lack of free will. Responsibility is essential for both a functioning society and for creating the satisfying life we all want. Neither can happen without it.

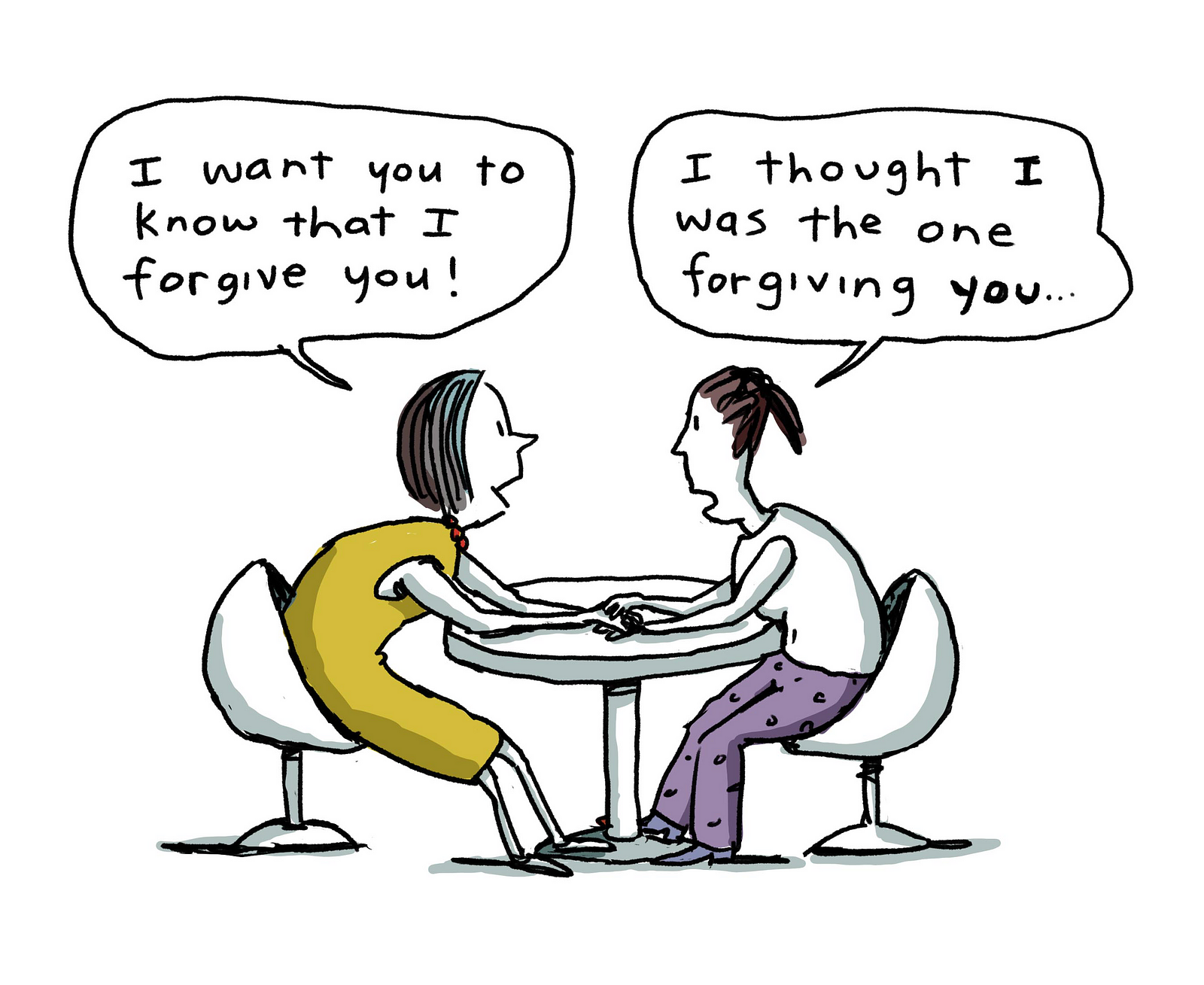

But we never need blame.

Not for ourselves or anyone else.

We are who we are. We can deny or embrace it. Fortunately, being who we are is a very, very cool thing to be. We’re jam-packed with human wonders, quirks, and powers unique to us. Our graceful dumb luck gives us everything we need for a satisfying life. Even when we are totally miserable, there is a rich, exhilarating playground with our name on it, waiting for us to let ourselves off the hook.